Architecture

Towards a Definition of San Diego Modernism

In hopes of addressing a number of opinions, may the following serve to raise new questions and alleviate concerns.

By Keith York

As in Europe, early in the 20th century American artists, craftsmen, landscape designers, architects and patrons alike, broke free from historical styles. Against the rules of composition, symmetry, proportion and ornament, modern architecture became a force of straightforward, rational and clean design. Like elsewhere, San Diego Modern Architecture fought the Beaux-Arts, Victorian and Edwardian traditions, instead seeking service and problem-solving as its aim. Using advanced building technologies, a focus on integrity of structures and materials, research and experimentation, and a new moral compass of the living environment (among other design strategies, architects sought a seamless integration of the built environment and landscape), architects and planners alike moved swiftly to change the face of San Diego’s built environmentAs in Europe, early in the 20th century American artists, craftsmen, landscape designers, architects and patrons alike, broke free from historical styles. Against the rules of composition, symmetry, proportion and ornament, modern architecture became a force of straightforward, rational and clean design. Like elsewhere, modern, or contemporary, architecture of the times fought the Beaux-Arts, Victorian and Edwardian traditions, instead seeking service and problem-solving as its aim. Using advanced building technologies, a focus on integrity of structures and materials, research and experimentation, and a new moral compass of the living environment, architects, designers and planners alike moved swiftly to change the face of San Diego’s built environment.

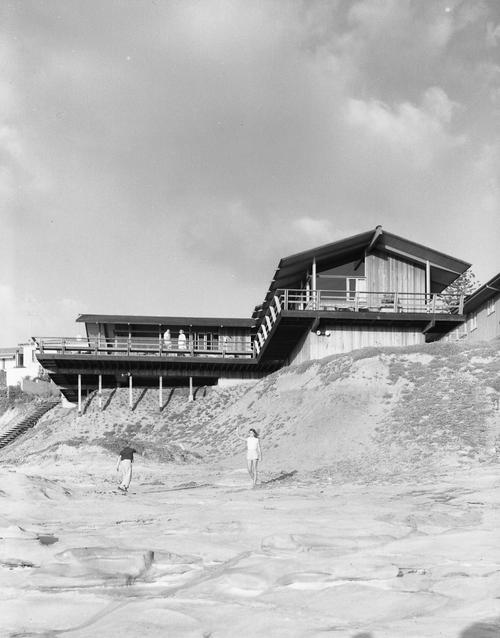

Modernism in San Diego, as in other burgeoning U.S. cities, was influenced by the earliest pioneers such as Mies Van Der Rohe, Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Adolf Loos, Louis Sullivan, Irving Gill and Frank Lloyd Wright. In the early decades of the 20th Century we find the birth of a regional modernist identity with Irving Gill’s early “cubist” structures such as Scripps Cottage (1912) and R.M. Schindler’s Pueblo Ribera (1923). While pre-World War II modernist architecture quietly established its foundation in San Diego, following the War, Lloyd Ruocco would play a pivotal role in welcoming modern architecture to the area through his own architecture, writings, lectures and encouragement of young architects’ ideas. His ideas took hold as demand for housing, as well as civic and commercial buildings increased exponentially with a changing local economy, post-war optimism and the growth of peace-time industry here. San Diego’s local climate, politics, finance industry and technology worked together to push architect and client forward rather than re-interpreting the past.

During much of the 20th century, the most progressive, innovative, contemporary architecture would later be deemed modernist. What was contemporary architecture during the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s is now viewed as modern – just as today’s progressive architecture may someday be referred. San Diego’s modernist architecture has always embraced a simplification of form, in part by eliminating ornament. Among the key design strategies, architects sought a seamless integration of the built environment and landscape as new thinking embraced our temperate climate.

Also driven by changing building technology and engineering, local modern architecture embraced developments in steel, glass, concrete, plywood and fiberglass. San Diego modernism can be described in part by the use of concrete flooring, large expanses of glass welcoming the landscape indoors, wood and steel structural elements allowing open floor plans, as well as carports, entry courts and patios that function as outdoor rooms. In original condition, buildings include steel, aluminum, fiberglass, plywood and plastic structural and functional elements such as household fixtures. Exteriors include glass walls, fine stuccos, plywood siding, board and batten and tongue ‘n’ groove building materials and techniques.

While many modern structures in San Diego are noted for their rectilinear geometry, the rejection of unnecessary details, and adoption of honest expression of structure drove much of this. Working against historicism, meant to embrace the principles of materials and functions of a project and its site. A select group of San Diegans embraced this progressive, forward momentum in design ideology, lifestyle philosophy as well as tangible influences like technology, contemporary design, building codes, financing, and land availability. Local architects Lloyd Ruocco, Robert Mosher, Russell Forester, Eugene Weston III, Dale Naegle, Bill Lewis, Richard Wheeler, Hal Sadler, Homer Delawie, Robert Jones, Henry Hester as well as a host of outsiders like Richard Neutra, Edward Durrell Stone, Harwell Hamilton Harris, Charles Luckman, Albert Frey, A. Quincy Jones and Louis Kahn brought their varied interpretations of Modernism to San Diego’s 20th Century built environment.

All the while, on a parallel track, are other organic architects following the tenets of Frank Lloyd Wright, Antoni Gaudi and Louis Sullivan. Among them, John Lloyd Wright, Sim Bruce Richards, Loch Crane, Frederick Liebhardt, Kendrick Bangs Kellogg and James Hubbell embraced nature as their inspiration not only in materials and form, but in siting, sustainability, flexibility and humanism. Within local organic architecture we find while the form may be less rectilinear, one can see, as plane as a fiberglass Eames chair, the essence or soul of each built project.

Have an idea or tip?

We want to hear from you!

email hidden; JavaScript is required

Architecture

Towards A Definition of Post-Modern San Diego

Architecture